Unsurance: California Homeowners and Utilities Face Off With Fire

In Brief

Fire has raced forward into the path of California home construction.

Homeowners and the utilities who serve them can't affordably find insurance .

With caps on insurance rates and spiraling risk, policymakers and policyholders face a reckoning.

The year 2020 stayed full of oversized news, from the continuous fight against a global pandemic to a pivotal and highly divisive presidential election. Among this news, national outlets paid some attention to the record wildfires in California. However, given that every subsequent year seems to break this record, its ramifications can become hard to discern. Utilities in California now face unmanageable insurance costs, as do homeowners in the state’s interior- and experts say clean energy costs must rise to absorb the insurance expense. No solution appears clear.

Frequent and Devastating Wildfires

This year has seen the largest wildfire season in California on record with over 9,000 fires burning across 4 million acres, or approximately 4% of the state's total land. The wildfires have also set a record damaging or destroying over 10,000 buildings in the state. The widespread destruction has forced tens of thousands of residents to evacuate.

A threat to life and property thus became almost daily, overwhelming the insurance system. Behavior may pop up as a vivid precursor to fires- we've read about “gender-reveal parties” in the woods- but more systematic factors cause this trend. To learn more about why wildfires in California have become more frequent and destructive, I spoke with Dr. Anu Kramer, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who is an expert on the subject.

Dr. Kramer noted that while cyclical wildfires are a natural part of California’s ecosystem, climate change has made the region hotter and drier, which increases the likelihood of fires. Insurance underwriters and scientists balk at how quickly this change is occurring. California’s summers are 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than they were in the 1970s and the number of heatwaves has increased from four to nearly ten per year.

Climate change, however, is only part of the story behind increasing wildfire destruction in California. The other driver is increased human interaction with the wildland urban interface (WUI). Dr. Kramer’s research has determined that the WUI, where human settlement ends and wilderness begins, includes 75% of the buildings destroyed by wildfire in California. People have modified the WUI landscape at the expense of the natural ecosystem’s balance. “Fire suppression efforts over the last century led to increased understory fuel build up, so when there is a fire it is of more severe. Additionally, fire suppression in the Sierra Nevada led to a tree species shift away from the pines that are adapted to a naturally frequent wildfire cycle towards conifers that are not.”

These conditions still need an ignition source, and that’s where human behavior becomes a factor. Human activities account for over 90% of the wildfires in California and the leading causes include equipment use (eg chainsaws), fires that got out of control and power lines.

Electric utilities in particular have been at the center of the conversation after a problem with PG&E’s equipment ignited the deadliest wildfire in California history, responsible for 85 deaths and the destruction of nearly 20,000 buildings including 14,000 homes In the wake of the devastating fire came a tsunami of claims against PG&E, mounting to an aggregate $50 billion, that forced the company to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy. But PG&E hardly stands as a rogue actor: state investigators believe that power lines providing electricity to the WUI cause about 10% of the state's wildfires.

A Tale of Two Markets

Insurance providers in this market have seen profits vanish. These companies generally model the likelihood of different risks using historical claims associated with that risk. The models failed to absorb climate and ecosystem changes. In 2017, the California insurers paid more than $2 for every $1 they collected in premiums and the wildfires from the past two years alone wiped out 25 years of the industry’s profits. With the record fires and destruction in 2020, it is likely that this year will be even worse.

The insurance industry, woefully aware that the status quo is financially unsustainable, has made efforts to correct this imbalance in both the commercial and residential market. These two markets, however, work very differently with the commercial insurance operating within a relatively free market while residential insurance is highly regulated.

Utilities buy commercial insurance through the surplus line market, where rates respond quickly to changes in risk, supply, or demand in the absence of government rate-setting. While this means that insurance premiums reflect market conditions, it can also lead to high volatility in pricing. Energy utilities in California also are pressured by the “inverse condemnation”, a doctrine written into the state constitution that holds utilities responsible for damages resulting from wildfires in which their equipment is found to play a role, even if the company follows best practices. This risk inflates rates further.

Unlike commercial insurance, most residential insurance is part of a government rate regulated market. Insurance premium hikes are constrained by California’s Proposition 103 regulatory system that requires rate increases to be approved by regulators and prevents insurers from using the latest catastrophe modeling projections. This system has made the price of premiums relatively sticky and while costs are expected to increase by 6.9% this year (the maximum increase without a public hearing), far more is needed to fix the imbalance.

Energy Utilities Challenged by Soaring Insurance Prices

The increasing financial risk posed by wildfires has corresponded to a dramatic shift in the price of insurance for utilities and independent power producers. I had the chance to talk with Sara Kane, a Senior Vice President at Beecher Carlson in the energy utility insurance industry, about how her market has responded to wildfire risks. Since the surplus line market is not rate regulated, insurance prices have soared over the past 5 years. In Sara’s experience, “insurance costs for commercial clients in the WUI are going up to 50-100% annually to account for heightened natural disaster risk.” She views this incredible price increase not as an insurance bubble, but rather as a market correction.

Insurance companies in this market have adjusted models to account for higher loss history and to incorporate their expectations that the wildfire related payouts will continue to rise.

The market may be a more accurate representation of the changing wildfire risks in the WUI, but some might argue that it is too responsive, making the financial planning for utility projects difficult to estimate. Sara recalled that an independent power producer in negotiations for an insurance plan saw the price increase each time a major natural disaster hit during the negotiation period. Given these conditions, her clients normally would consider reducing their insurance policy; however, their hands are often tied by the project lenders who require a set level of coverage as part of the project financing agreement. Since these projects require full coverage, the demand remains high as the risk appetite of insurance suppliers in the region shrinks leading to extremely high premiums.

This has also been a more significant issue for smaller project developers who have less financial flexibility and face higher costs compared to more established energy providers. Sara noted that in the insurance game, “there are definite economies of scale and smaller energy projects face greater hurdles in obtaining affordable insurance.” This is due to a combination of factors such as the ability of larger energy providers to spread insurance risk across a wider portfolio of assets, better insurance rates for more established market players, and the smaller impact an increase in insurance cost would have on a larger scale project.

The renewable energy market faces greater insurance pressures even than traditional utility projects, and some solar projects have seen premiums increase annually by up to 200%. The projects also face the challenge of lower deductibles than traditional projects. Sara says that this is due to both the historical precedent of renewables offering lower deductibles and an industry view that renewable energy is more exposed to natural catastrophe perils, particularly solar energy projects. Jason Kaminsky with kWh Analytics and Sam Jensen with Stance Renewable Risk Partners outline the challenge, noting that “during soft market conditions, deductibles under all-risk insurance policies were as low as $10,000 or capped at 2% to 5% of the total claim value for catastrophic perils. Deductibles have now shifted to much higher dollar amounts, and deductibles are now typically 5% of the total asset value for catastrophic perils.”

While the fiscal dangers of “free market” determined insurance continue to loom larger, the financial burden has not yet prevented further energy project development in the region. A driving reason behind this, according to Sara, is that energy utilities that have begun construction are already locked into an insurance agreement. With steel already in the ground, an agreement signed, and a requirement from their financers to insure the project, they are captive to changes in market conditions. The increased cost of insurance is generally paid out of the equity portion of the project’s funding, which means lower returns for investors.

The energy project insurance market in 2020 is definitively a seller’s market and while some in the industry are of the opinion that these trends are temporary, Sara believes that natural disaster risk will continue to inflate the market.

The Grass Isn’t Greener on the Residential Side

The evident issues of the commercial insurance market might present an enticing case for a strictly regulated market; however, the residential insurance market in California demonstrates the flaws inherent to that approach. As noted before, the state government enforces strict rate ceilings on insurance costs that have prevented the price from adequately adjusting to the increased wildfire risks. This has been, in the short term, a beneficial system for homeowners in the WUI as their insurance premiums remain low and the increased wildfire risk is not accurately impacting home values. This status quo, however, is unsustainable for insurance companies and to avoid further losses, they are trying to abandon the region entirely. The insurance industry’s retreat from the WUI is borne out in the numbers as 235,250 policies discontinued last year, a 31% increase from 2018.

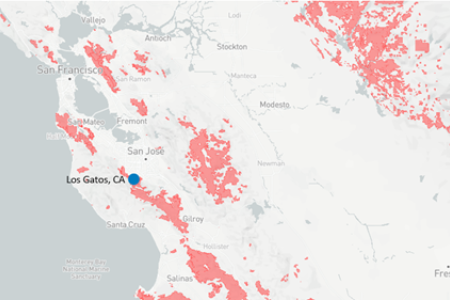

The numbers paint a bleak picture, but to understand what this has meant for individuals in the WUI, I spoke with John Smith (a pseudonym) about his experience with insurance. John Smith has been a homeowner in Los Gatos, a community considered to be in a “very severe” fire hazard zone, for over 30 years and up until recently, he has had no issues with his home insurance.

At the end of 2019, John received a vague letter informing him that his insurance company would not renew his plan this year and that he had only six months to find a new plan. John, surprised reached out to his insurance company to hear more about why they were really dropping his plan. John recalls the conversation as “beginning with a lot of mealy-mouthing, but by the end they just told me that it was because I lived in a wildfire prone area. I think that I was part of a wider culling in response to the Camp Fire.”

More than 1.1 million California buildings, roughly 1 in 10 in the state, lie within the highest-risk fire zones in maps drawn by the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. John’s home in Los Gatos is within the “very severe” hazard zone (shaded red) as determined by the state.

John was able to quickly secure another insurance plan for his home in Los Gatos through a different insurance group. However, they canceled his insurance plan less than a month after the ink had dried. Their official reason for cancelling was that they had not done a thorough home inspection prior to the insurance plan agreement. According to John, the insurance company had tried to schedule a home inspection with him, but his voicemail was full. At this point in the interview John wryly noted “I highly doubt that happened as I only get about three calls a year.”

John did eventually find a third insurance company to offer him a plan. Due to the rate-setting protections in California, his insurance costs remain reasonable, but he is not out of the woods yet. In early November of this year, John received a letter from his new insurance company informing him that they will be conducting a home inspection for wildfire risks.

John rated his experience with the insurance agencies as “a negative 14 on scale of 1 to 10”, and he is not alone in his concern and frustration. The California Department of Insurance noted that complaints have more than tripled between 2011 and 2016, and have likely increased even more since the study was conducted. John has had two relatives who lost their homes to wildfires in California recently and so while his situation is not ideal, he maintains a positive outlook saying that, “if this is the worst that happens to me in my life, then I consider myself blessed.”

Policy Response

In the WUI, the state government has been acting to protect homeowners from an insurance cliff. Last year, Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara announced a yearlong moratorium preventing insurance companies from cancelling or refusing to renew insurance policies of over 1 million homes that were near the previous year’s wildfires. On November 5th, this order was extended for another year and the scope was expanded to now include 2.1 million households in or near areas hit by this year’s wildfires.

Additionally, if homeowners do lose their private insurance they can still buy into the government backed Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plan. To be clear, this is generally more expensive and covers less in damages. And questions remain as to what the sustainable long-term solution will be.

The state has also tried to shelter utilities from increasing insurance costs. Last year Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law the creation of an $21 billion insurance fund for the state’s three investor-owned utilities — PG&E, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric. Even though participation in the fund would require the utilities to pass annual safety checks, this proposal was immediately met with fierce opposition from those who believe that it will reduce utility accountability. Additionally, the capital, half from utility investors and half from ratepayers through bonds, has prompted complaints from Assemblymember Marc Levine, among others, about investors’ share of the costs. These actions do not extend to smaller power-producing projects that are still at the full mercy of the private market.

Looking Forward

As we adjust to this new reality, people have begun to think about how to mitigate the danger that wildfires pose. A straightforward but unpopular solution would be to relocate utilities and homes in these fire-prone regions to safer communities. Given the unlikelihood of a mass evacuation of millions of homes and the abandonment of billions in assets, communities will have to adapt and become resilient to wildfires. These measures can range from simple actions to reimaging the insurance system.

For homes, moving from wooden structures to fire resistant brick or clay would be a good start. Landscaping can also make a difference, and CAL Fire has a list of fire resistant plants and trees that they recommend for people living in the WUI. For utilities, however, even the simple changes would cost a considerable amount. The estimated cost for upgrading PG&E’s electrical grid to reduce future wildfires range from $40-50 billion. These high costs apply to other utility and power projects that would have to pay up to $5 million a mile to move all transmission power lines underground.

Distributed generation and microgrids provide a promising path for communities in the WUI as it could reduce the use of power lines that cut through sensitive regions. The California Public Utility Commission proposed in early December $350 million for clean energy microgrids to reduce wildfire risk, but implementation concerns remain. These microgrids rely on batteries that can only cost-effectively store about four hours of power and require massive amounts of solar PV to charge them.

These prudent actions can help improve the state’s resiliency to wildfires, but insurance regulation reform is still needed. Shifting to a more responsive residential insurance market in the WUI will not happen overnight and should not place undue burden on those already in the region. Dr. Gireesh Shrimali, a research scholar at Stanford University, advocates for a universal wildfire insurance system to make the system more sustainable by spreading the cost across homes that are at high risk as well as those that are low risk. This would provide insurance companies with a more profitable model as premiums would also be coming from customers not likely to see payouts, and would guarantee wildfire insurance to everyone. To avoid the clear moral hazard and unfair burden shifting that could occur in a flat-rate universal system, the model still uses risk-based pricing.

This would likely dampen house prices in high-risk areas but adjusting home prices to the reality of wildfires is likely overdue. Other options to address the residential insurance could be to provide economic incentives to people to move to a safer community and to provide more affordable housing in urban areas that are currently pricing out many families. Dr. Shrimali also suggests “a complementary policy to institute smarter land use policies that limit development in risky areas or at the very least require more disclosure of risks to potential home buyers.” This would prevent overdevelopment of these high-risk regions without forcing a mass evacuation for those already living there.

Energy utility and project insurance already reflects the wildfire risk but faces an impending affordability issue. The state government is providing emergency funds for the state utilities and larger energy providers may be able to afford the insurance for now, but it will likely price out smaller renewable energy projects in the future. This issue is not endemic to California and has been grappled in other fire prone regions such as Australia, but so far there has been no clear solution. Short of federal funding for insurance of small-scale renewable energy production, the economics seem unfavorable for the long-term prospects of these projects in fire prone regions.