New Customers for Microfinance Can Accelerate Off-Grid Solar

The growth of the off-grid solar appliance market hints at untapped opportunities for investors to support energy access goals. According to the Global Off-Grid Lighting Association, in the first half of 2017, over 3.5 million such products were sold globally, yielding nearly $100 million in sales. Over 8 million products were sold in 2016. These figures represent impressive headway toward providing modern energy services to the poorest members of global society.

International targets set by the United Nations also show that there is global support for this industry. But the road ahead is a long one. Over 1 billion people still lack access to reliable, modern energy services. Over 80 percent of them live in rural areas, according to World Bank data.

Microfinance, long-heralded as the solution to pulling people out of poverty through credit building and financial inclusion, could help. But providers will need to reframe what they are financing.

Understanding the Traditional Microfinance Model

According to the Nobel Prize website, as early as the 1970s, microfinance existed to provide small-business loans for traditional enterprises such as food vendors and textiles, industries that have existed for over a century.

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) have historically viewed women as attractive target clients, according to the International Labour Office. Many microloan recipients have been women.

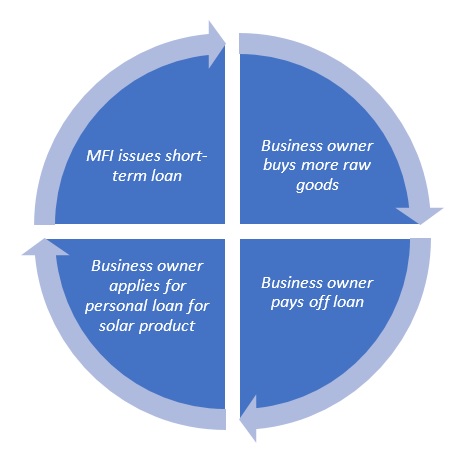

Microloans provide short-term injections of working capital. In 2015, Compartamos reported average loan sizes of just under $450.

Regardless of their size, microloans allowed small enterprise owners in traditional industries to start building their credit and growing their businesses.

Applying Microfinance to Energy Access

So how has the microfinance industry aligned with energy access? Ajaita Shah, founder and CEO of energy-access company Frontier Markets, said MFIs have traditionally financed solar-powered lighting.

For example, a small Tier 1 system which has multiple lights with USB charging costs just over $200. Simple lanterns may cost only $15.

Shah said that in the six or so years that MFIs has financed off-grid solar, there has been little correlation between lighting access and economic productivity. The thesis that buying a solar light will lead to more productivity is unproven.

Therefore, microloans have been put to work for a mix of business uses (such as sewing machines) and household consumption (such as solar lanterns). This narrowed the pool of eligible candidates to women who already had traditional businesses and were interested in leveraging that credit to buy lanterns.

“When microfinance got involved with energy access, they got involved in… consumer loans. [Business owners] essentially took out consumption loans on the backs of their credit histories from their businesses,” Shah said.

Shah further elaborated that the reason the MFIs were willing to issue the loans was that the consumption portion of the loan was only 10-20 percent of the whole loan. There is also a fundamental question regarding whether MFIs should be responsible for pure consumption loans.

In this context, a consumption loan is one where the loan is used to buy something that does not directly generate more revenue. In contrast, a business loan is used for capital expenditures — such as sewing machine purchases — which are directly revenue-generating.

While the prospects are encouraging, this financing method only addresses small business owners who already have some credit history. As the economy evolves and new markets emerge, development practitioners are asking themselves how microfinance can support new industries among low-income communities.

Building a Community-Centric Approach to Solar

Frontier Markets, a for-profit social enterprise promoting energy access in India, is taking a community-based approach to off-grid solar distribution.

Shah, an Indian-American entrepreneur, founded the company in 2009. It has since been recognized by organizations like National Geographic and Sustainable Energy for All for its groundbreaking work enlisting rural women in Rajasthan, India to serve as solar ambassadors and entrepreneurs within their communities. (This is just one of Frontier Markets’ multiple initiatives.)

Local women called the Solar Sahelis are trained to repair products. Their presence in the villages where they work reinforces trust. These aspects of the Solar Saheli business model swiftly overcome two major barriers in off-grid solar appliance distribution: lack of recourse if products break and lack of trust in new technologies. The Solar Sahelis also help Frontier Markets anticipate consumer demand for different solar appliances.

The model simultaneously addresses multiple sustainable development goals: solar deployment, poverty reduction, and gender equity.

Microfinance has a long track record of promoting gender equity by teaching women how to make financial decisions and then giving them the means to do so. There is also consensus among academics that clean energy has enormous health and social benefits for women at home.

Disrupting the Status Quo

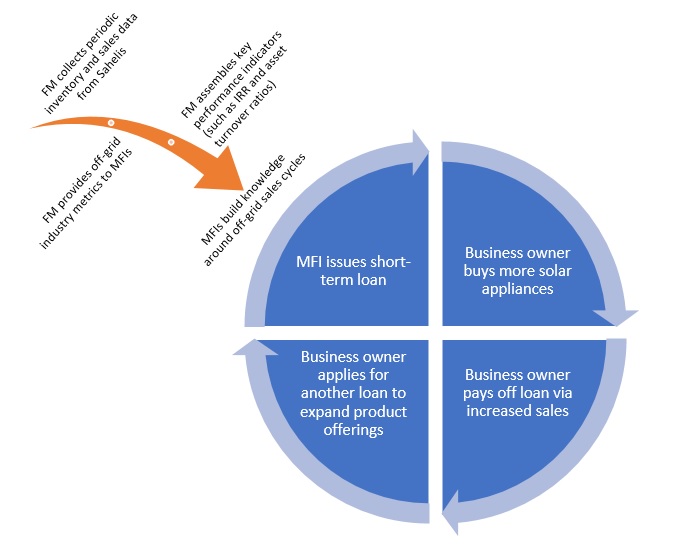

Shah’s Solar Saheli model could be financially disruptive if it is able to overcome one glaring barrier: MFIs don’t understand the off-grid solar sales cycle well enough to issue loans to the Solar Sahelis. Nor do the Solar Sahelis have credit histories; prior to joining the program, the women had annual incomes between $0 and $150.

Shah hopes that by collecting detailed inventory and sales data, Frontier Markets can show lenders that the Solar Sahelis are bankable clients with predictable cash flows. She intends to demonstrate that the solar appliance market can be as viable as more traditional enterprises financed by MFIs.

“What does this look like in terms of really trying to understand the rotation of inventory and working capital?” Shah asks. “Our thesis on the energy sector is that we're not going deep enough to crack this. We keep talking about why everyone needs access to finance, but we're not actually doing the deeper dive to understand the financial needs.”

If Shah is successful, the Sahelis will have more inventory on hand at any given time and be able to grow their own businesses quickly. MFIs will also be better-informed and capable of expanding their investments across the most underserved developing economies. If the business is lucky, next year’s microloans will extend beyond vegetable seeds and fabric — they will finance the next wave of clean energy deployment with women leading the charge.

Join our LinkedIn group to discuss this article. You may also email the author directly using our contact form.