How Can the Supply of Community-Shared Solar Meet the Demand?

Nonprofits face a unique challenge in the solar-development market. According to a report by Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA), the demand for community-shared solar is soaring, but supply cannot catch up due to a lack of financing options.

Because these installations are relatively new and unfamiliar projects, the SEPA report found that banks and investors are hesitant to provide the solar developers with funding. They also do not want to make traditional low-interest loans. The small size of community-shared solar projects makes them less attractive to potential investors than they might be if they were larger.

As a result, many solar developers have devised innovative strategies to navigate the financing process.

The report includes interviews with six solar developers across the country that successfully financed community-shared solar projects.

Two of those organizations, Michigan Energy Options (MEO) and BARC Electric Cooperative, are nonprofits that have developed small-scale community-shared-solar installations. They offered key insight into the development process, sharing their experiences and advice with other nonprofits considering community-shared solar.

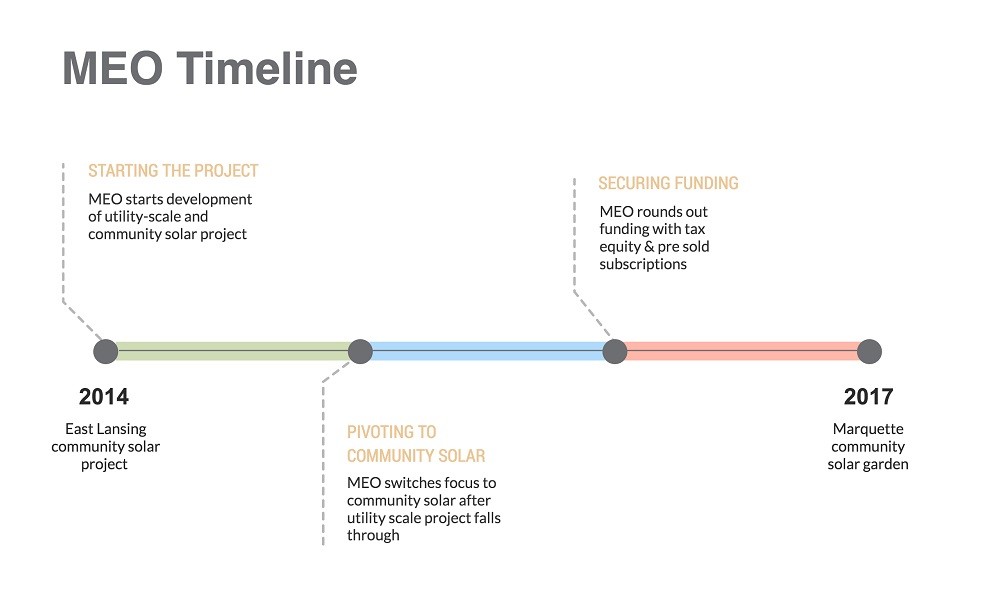

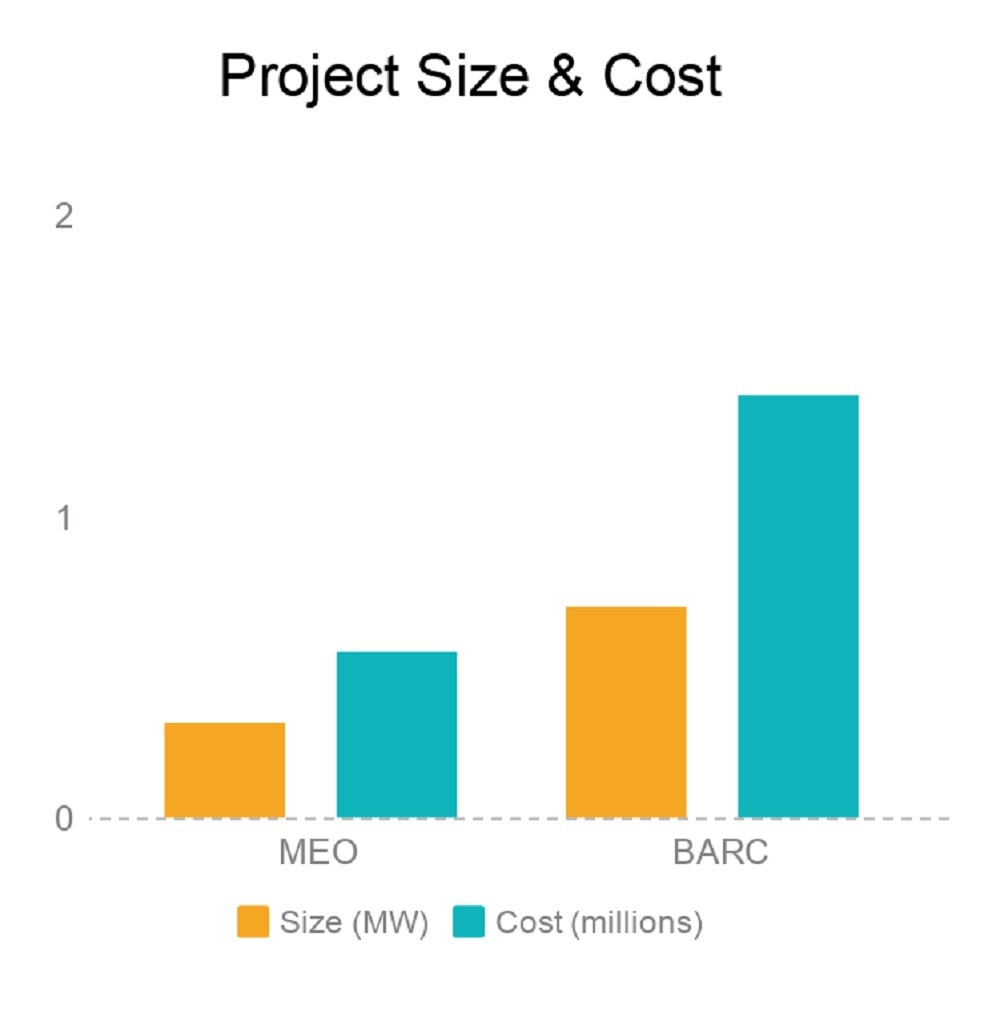

John Kinch, executive director of MEO, said that MEO initially decided to pursue both a utility-scale project and a 300-kW community-shared solar project. However, he said that the plans for the utility-scale project fell apart. The solar financiers who were interested in funding both projects lost interest when MEO chose to move forward with the smaller community-shared-solar project.

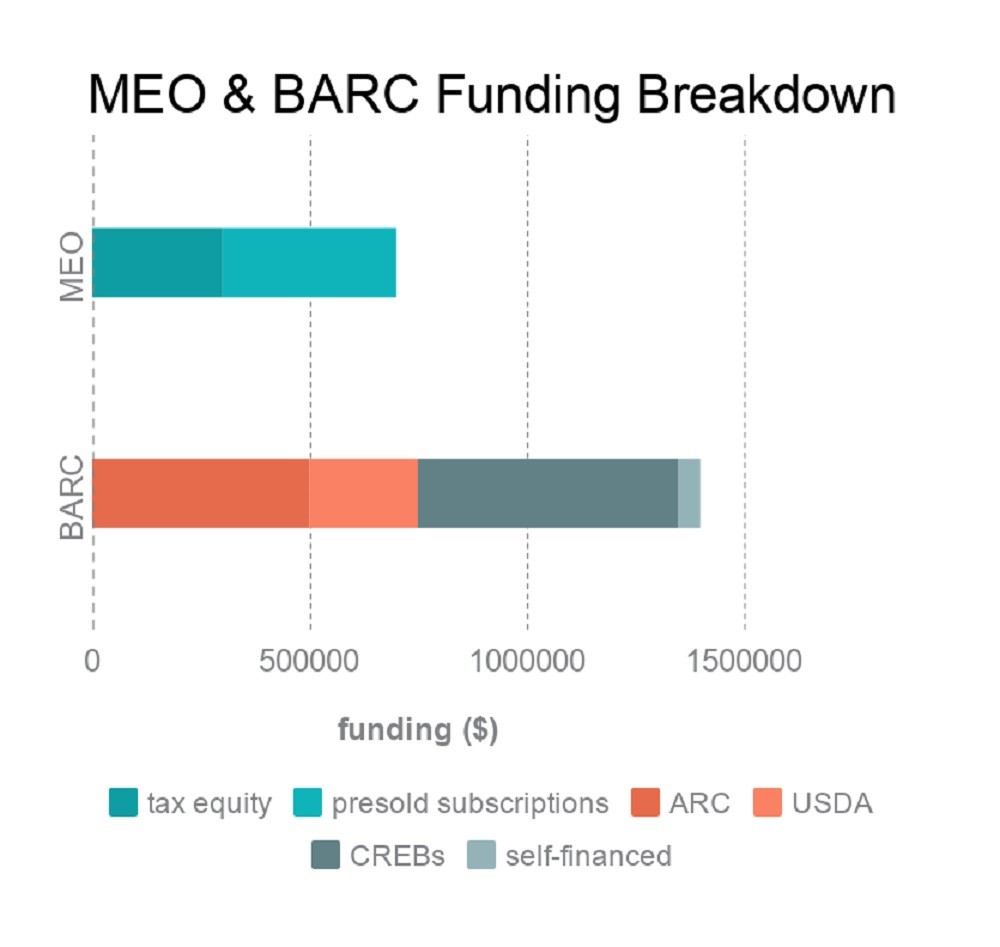

According to Kinch, MEO and its partners managed to secure funding for the 300-kW project from a solar-development financier and tax-equity investor Pivot Energy after a long search.

In the process of gauging interest for the project, Kinch found that people and businesses in the community were excited about it. However, they wanted to see the project completed before making guarantees. He said that as a result, the development process stalled as people who expressed interest chose not to pay for subscriptions until the installation was constructed.

Instead of employing a model of trying to sell subscriptions early in order to trigger tax-equity investments, Kinch said he advises securing a significant number of acres beforehand and then selling subscriptions once the project development has made progress.

Given the small size of the installation, MEO had difficulty finding tax-equity investors interested in financing the community-shared solar project, Kinch said. He said that fortunately, MEO successfully partnered with Pivot Energy, a corporation interested in the smaller 300-kW project and large enough to take advantage of the Investment Tax Credit as a tax-equity investor.

“It was very fortunate for us because for the most part, with anything less than a MW, you’re going to have trouble finding tax-equity investors,” Kinch said.

MEO’s complementary partnership with Pivot Energy enables them to spend time on the ground and have conversations with local decision-makers.

According to Kinch, “Aligning a nonprofit with a good for-profit is probably the sweet spot right now.”

Kinch said he advises developers to consider projects hovering around one MW or greater if they want to attract funding. The transactional costs and various fees of negotiating such a deal reduce the value of community-shared-solar projects that are sized under one MW. This discourages investors.

As a result, Kinch said that even with space constraints restricting the size of the project, it would be worth it to find another site so that the total size of the project exceeds one MW.

“Community solar solves a market failure,” Kinch said. “It allows people to take part in local solar not necessarily located on their property.”

Kinch said he saw that many people in the community can’t get solar on their roofs due to various complications: they don’t own the roofs, the roofs don’t face south, or trees near the homes block sunlight. He said that MEO’s project allows customers to lease as little as one panel, sparing them the risk of making a significant capital expenditure to purchase and install solar panels on their own.

Being a nonprofit also has its advantages. Having been in business for 40 years, Kinch said MEO has a strong reputation and deep ties with its community.

“We’ve been involved in this community and in Michigan for a long time,” Kinch said. “I play on the fact that we’re a nonprofit. Our goal is to encourage market transformation, provide transparency, provide good information to help educate people, and to spend a lot of time in front of public groups explaining things and dealing with people’s misconceptions. [...] It’s in the DNA of nonprofits to do this kind of work.”

Kinch said he advises other nonprofits to stay close to the ground and connected to the community. “Go out and ask people questions about what they want their community to be and what’s their own vision about what the future looks like,” he said. “Then, from that, you can have questions around clean energy and solar.”

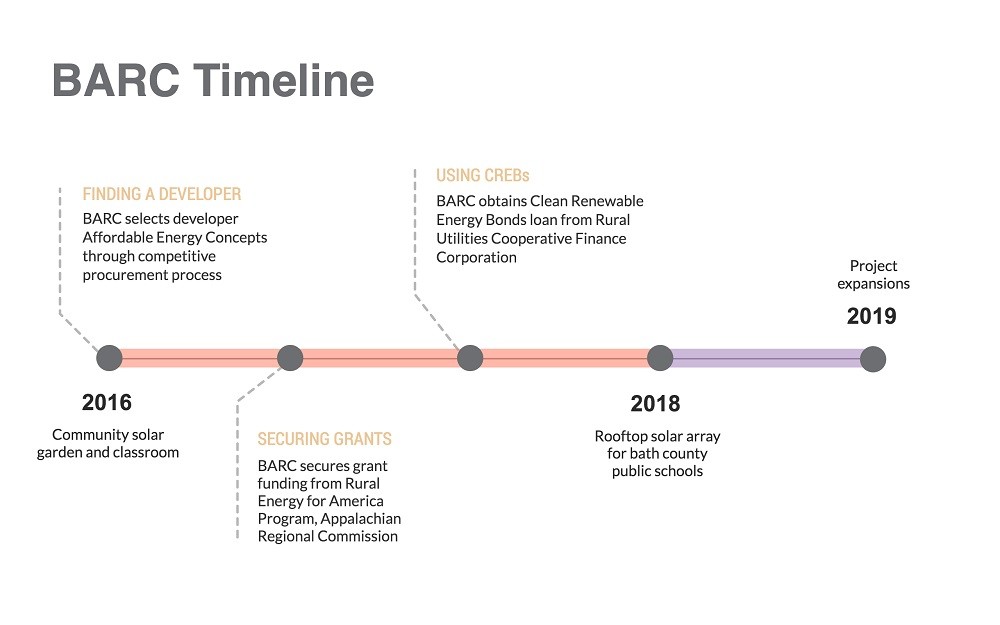

BARC Electric Cooperative has been managing and operating a community-based-solar garden since 2016, according to the SEPA report. To secure $1.4 million in upfront capital for the project, CEO Mike Keyser said BARC considered several unique financing strategies: seeking out grants, setting up a for-profit subsidiary, and using Clean Renewable Energy Bonds (CREBs).

The SEPA report explained that the co-op first sought grant funding through the Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). Prior to applying for the REAP grant, Keyser said, he focused on building relationships with local United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) representatives from the Richmond office. This eventually led to a $250,000 grant. He said he recommends that other rural developers connect with the local USDA office’s State Rural Development Energy Coordinator. This is the first step to securing grant funding for community-shared-solar projects.

Keyser said that at the time, solar development was a novel concept in Virginia, with only a handful of utility-scale-solar installations in the region. In applying for a community-infrastructure grant, he explained to ARC how the concept of community-shared solar operates and how community-shared-solar projects can benefit local residents.

He found that ARC was concerned about how community-shared solar might contribute to economic development. In addition, ARC wanted to know how stable costs for electric consumption could be ensured for residents and businesses. Demonstrating how BARC’s solar garden would produce these effects was essential.

The addition of the learning center to the solar array also made the positive impact of the project tangible. Keyser said that demonstrating a community benefit played a role in helping the co-op obtain the $500,000 grant from ARC.

The SEPA publication reported that after being awarded $750,000 from ARC and USDA grants, BARC continued its search for financing options. As a tax-exempt nonprofit, the co-op sought ways to access the benefits of the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) by forming a for-profit subsidiary. However, the BARC CEO said the burdensome administrative and legal costs largely mitigated and outstripped the advantages of the ITC due to the small scale of the 550-kW project.

According to Keyser, BARC began considering alternatives to the tax credit to avoid prohibitive soft costs associated with setting up a for-profit entity. It ultimately chose to fund the remaining $600,000 through CREBs.

According to the United States Department of Energy website, CREBs avenue of funding is no longer available with the repeal of the CREBs program under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Nonetheless, Keyser said emphatically that the co-op’s existing relationship with a bank, the National Rural Utilities Cooperative Finance Corporation (CFC), proved instrumental in securing a loan.

The community-shared-solar project was a natural opportunity for the CFC to continue collaborating with BARC and create a favorable loan structure using the CREBs rebate.

“[The CFC] was a huge help because they had the expertise to navigate the CREBs process,” Keyser said. “Without them it would’ve been really difficult.”

According to Keyser, BARC began considering a small-scale project after seeing a lot of interest from members about solar. He said that co-op customers interested in solar initially discussed with BARC how the cooperative could facilitate and develop solar projects for them, but due to various factors such as high costs and shading issues, customers chose not to pursue solar.

Keyser said that as a result, BARC looked for alternative options, ultimately settling on a 550-kW community-shared-solar project with a subscription-based model. He said, “We wanted to fill a need we were seeing with our customers that wasn’t being filled. It’s a win-win for us and the customer.”

The success of the community-shared-solar garden has encouraged BARC to continue developing similar solar projects. Keyser said, “Community solar has led to lots of other discussions and opportunities and more solar since we built it.”

The BARC website says that after completing the solar garden, BARC developed rooftop-solar installations for school districts in the region. Keyser said that in 2019, the co-op plans to expand its existing projects, adding another MW. As long as there is demand, Keyser said, BARC will keep expanding and serving customers who want it.

Note: All of the graphs and charts in this article are based on the SEPA report data and were created by Brian Li.

To comment on this article, please post in our LinkedIn group, contact us on Twitter, or use our contact form.